The Saga of Muammar Gaddafi

Part One: The Sands Of Time

It was September 23rd, 2009. I had a budding interest in politics, although the opinions which I held at the time neatly conformed to the typical neoconservative model, even though I was somewhat hopeful of the prospects of our new Democratic President Barrack Obama, whose election, I considered, a step in the right direction for America. Anyway, I had some flavor of mainstream news on the television, and they were airing the United Nations General Assembly. As fate would have it, Muammar Gaddafi was at the podium addressing the world. And this would be the first exposure I had to the so-called evil dictator of Libya (aside from some American pop culture that regarded him as such).

It is a rather long speech but implore you to watch it for yourself. Gaddafi addressed many issues including: The hypocrisy of the UN Security Council, the invasion of Iraq, reparations Gaddafi negotiated the Italians to pay for their genocidal colonization of Libya (more on this later), Abu Ghraib, the assassination of Patrice Lumumba and JFK, land mines, man-made viruses and vaccine profiteering (my, this sounds familiar), and the continual Palestine/Israel conflict. Yes, it is a bit all over the place. My first thought after seeing this speech was: they’re going to kill this man. Time would prove this thought correct.

Whatever opinion you hold of Gaddafi at this moment, intrepid reader, for good or for ill, there is no doubt that he was, indeed, a revolutionary. And to understand a revolution - and, therefore, the revolutionary - it is important that we first understand the chain of events that make revolution inevitable. And to do this, we must turn back the pages of time.

Ancient Libya

The history of Libya is ancient and spans millennia. Libya was first inhabited by the indigenous people known as the Berbers (from which the English word 'barbarian' is derived) who, some have thought, first arrived in the area of Africa known as the Maghreb or al-Maghreb (Arabic for ‘The West’) 10,000 years ago. 1

That its northern coastline bordered the Mediterranean Sea, it was inevitable that Libya and the indigenous peoples which populated it would come into to contact with the great civilizations and empires of antiquity. In the 8th Century BC, the Phoenicians would establish Tripoli as a coastal trading post. Later the Greeks would establish a colony to the east known as Cyrene.

The fate of Libya and the ancient world would be decided by the Second Punic wars, in which Rome would emerge as the new Superpower of its day. To supply its bourgeoning population and empire, Rome would send its elite engineers to North Africa to terraform the desert landscape of Libya with aqueducts and wells which would provide enough water to raise crops of oats, barley and wheat. Rome's outposts would fall to the Vandals in the early 5th century, with aid of the indigenous Berbers who had long seen the Romans as foreign oppressors. The Vandals would also later fall to the Byzantines who desired to establish a Christian empire in an attempt to emulate ancient Rome.

In the 7th century, Arabs from the east would conquer Libya and bring with them their new religion - Islam. These Arabs would become to be known as the Bedouin. The Bedouin were a wandering, pastoral people raising flocks of sheep and goats who had no need for Roman Aqueducts. Thus, the infrastructure that had enabled much of the land to be farmed went into disuse and disrepair, and a culture of nomadic tribesman dominated the landscape.2

Although foreign powers would come and go, the customs of the Bedouins would continue for a thousand years relatively unchanged. These are the people from which Muammar Gaddafi descended.

Modern Libya

Libya would be of no great importance to the West until the beginning of the Second World War. The land was inhospitable, the heat was intense, the landscape was littered with venomous serpents and stinging scorpions, and, most importantly, believed to possess no natural resources. The Barbary coastline was known as a hub of piracy and Tripoli would be a center for the slave trade in the Mediterranean.

In the year 1800, US President Thomas Jefferson objected to any more payments to the Pasha of Tripoli. The United States had already paid Yussuf Karamanli 2 million dollars in tolls so that Christian fleets might access the Mediterranean. The Pasha would threaten the United States with war if the tolls were not paid. Jefferson responded by sending three frigates and a sloop to blockade the port, and one the frigates, the Philadelphia, ran ashore an uncharted reef and was forced to surrender its crew of 308 men. These Americans would be imprisoned for 19 months until Jefferson sent a small force of Marines to rescue them. The Pasha soon capitulated, and the hostages were released. This would mark the beginning of the end for the pirates of the Barbary coast.3

These events are celebrated in the hymn of the US Marines: "From the halls of Montezuma to the shores of Tripoli."

Europeans would, however, still avoid Libya, that is, until Italy seized Libya from the Turks in 1911, which they would occupy until the end of the Second World War. This era of occupation would be marked by atrocities committed on both sides and bloodshed in what would come to be known as the First and Second Italo-Sanussi Wars (1911-1917 and 1923-1931).

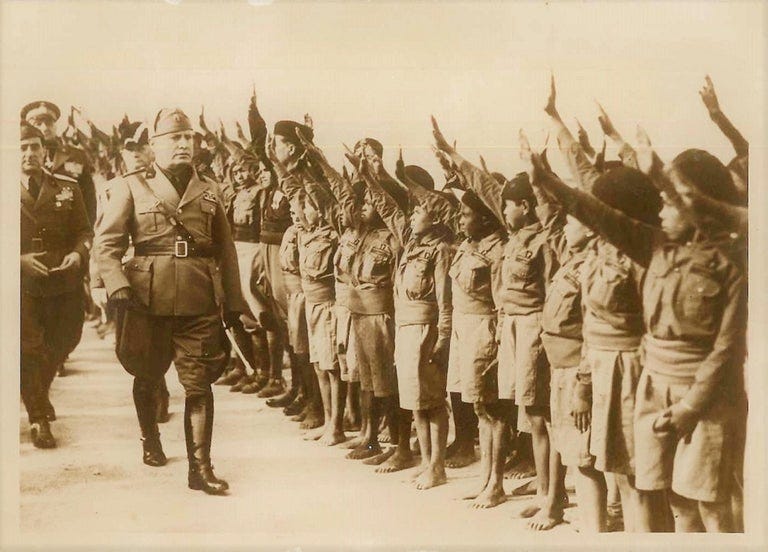

Mussolini wanted to make Italy great again, one might say, and establish his New Rome as a colonial power, turning Libya into the granary of the Empire. Italian settlers would come to Libya by the thousands, driving out the Bedouins, exploiting the land in the name of fascism. Bedouins would be sent on death marches to meet their pitiful fates in Italian concentration camps. 4 This war would gradually become a new crusade of Christians against the Arabs as Mussolini employed Christian soldiers from Eritrea to slaughter the indigenous peoples of Libya. Gaddafi's father would lose an eye fighting the Italians in this war and would be captured alongside his brother and sentenced to death, but ultimately, they both would be reprieved.5 It is estimated that 1/4 of the population of Cyrenaica was wiped out.6

Mussolini in Libya, 1937. Photographer unknown

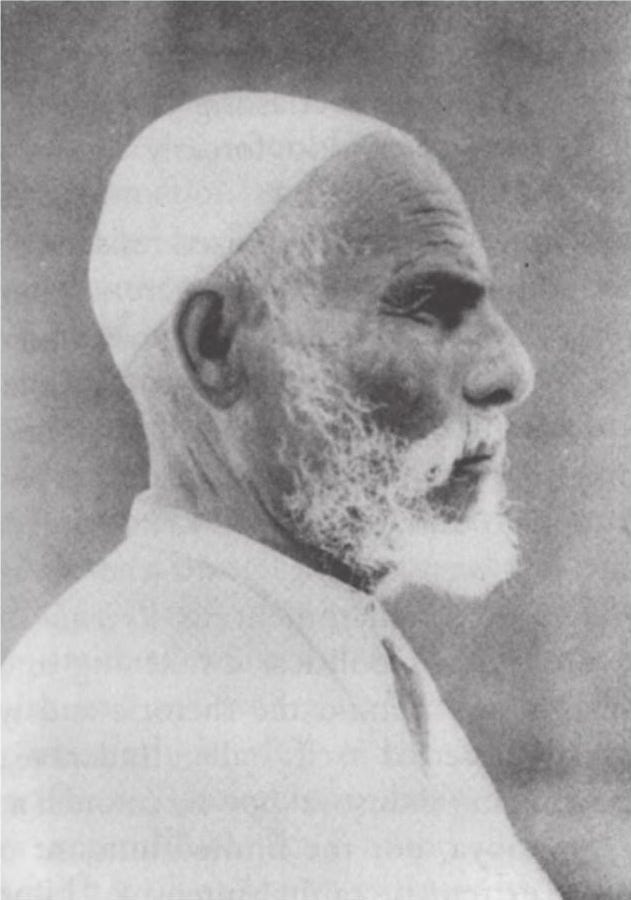

A notable figure from this war would be Sheikh Omar al-Mukhtar, a holy man in his sixties who would rise up to lead the Bedouins against the Italian oppressors, and who would later be revered by Libyans, and Gaddafi, as the father of the revolution. Outmanned and outgunned, the Bedouins, under the leadership of al-Mukhtar would engage in guerilla warfare, traveling by night and attacking the Italians at dusk, slitting their throats in silence and crawling under the barbed wire back to safety. This tactic would strike fear in the hearts of the fascists who would respond with such ferocity that the Second Italo-Sanussi war can be considered to be a genocide.7 Eventually, the Italians did capture al-Mukhtar, and he was publicly executed as thousands of Bedouins were forced to watch.8

Italian colonial administration of Libya- Dirk Vandevalle: A history of modern Libya. 2nd edition. Cambridge University Press 2012, p. 31

Fascism would ultimately face its defeat at the end of the Second World War. The British would be the de facto ruler of Libya for 8 years after the war - a war-torn country that was effectively a garbage heap of downed aircraft, barbed wire and unexploded landmines. Though Libya would be granted its independence by vote of the UN General Assembly on November 21, 1949,9 the British had installed their man on the inside - King Idris of the Sanussi Order, who had gained favor by his support of the British in World War II.

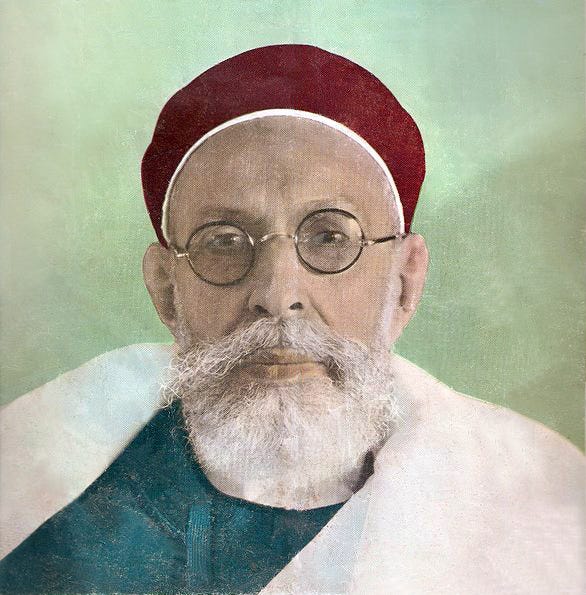

King Idris on the cover of the Libyan Al Iza'a magazine, 15 August 1965

Idris would rule the impoverished state from 1951 until 1969 when he was deposed in Gaddafi's coup d'état. His reign was marked by weakness and paranoia. In 1963 he would ban all opposition and make Libya an absolute monarchy.10 His fate, however, would ultimately be sealed some years prior in 1959, when oil was discovered in Libya. He would oversee the syphoning of Libya's natural wealth and resources by western corporations, lining his own pockets while leaving the people in destitute desperation.

The situation was ripe for revolution. It was only a matter of time…

Hsain Ilahiane (17 July 2006). Historical Dictionary of the Berbers (Imazighen). Scarecrow Press. p. 112.

George Tremlett (1 Jan 1993). Gaddafi: The Desert Mystic. Carroll & Graf. p. 40-44

George Tremlett (1 Jan 1993). Gaddafi: The Desert Mystic. Carroll & Graf. p. 35-36

Italian Genocide in Libya in the early 20th Century—Who knew? Now we do (arabamerica.com)

George Tremlett (1 Jan 1993). Gaddafi: The Desert Mystic. Carroll & Graf. p. 57

Second Italo-Senussi War - Wikipedia

George Tremlett (1 Jan 1993). Gaddafi: The Desert Mystic. Carroll & Graf. p. 60

George Tremlett (1 Jan 1993). Gaddafi: The Desert Mystic. Carroll & Graf. p. 62

George Tremlett (1 Jan 1993). Gaddafi: The Desert Mystic. Carroll & Graf. p. 78

Idris of Libya - Wikipedia

Excellent post! Your tone reminds me of Bill Bryson.